Role of pancreatography in the endoscopic management of encapsulated pancreatic collections – review and new proposed classification

Igor Mendon?a Proen?a, Marcos Eduardo Lera dos Santos, Diogo Turiani Hourneaux de Moura, Igor Braga Ribeiro, Sergio Eiji Matuguma, Spencer Cheng, Thomas R McCarty, Epifanio Silvino do Monte Junior, Paulo Sakai, Eduardo Guimar?es Hourneaux de Moura

Abstract Pancreatic fluids collections are local complications related to acute or chronic pancreatitis and may require intervention when symptomatic and/or complicated. Within the last decade, endoscopic management of these collections via endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural drainage has become the gold standard treatment for encapsulated pancreatic collections with high clinical success and lower morbidity compared to traditional surgery and percutaneous drainage. Proper understanding of anatomic landmarks, including assessment of the main pancreatic duct and any associated lesions – such as disruptions and strictures – are key to achieving clinical success, reducing the need for reintervention or recurrence, especially in cases with suspected disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome. Additionally, proper review of imaging and anatomic landmarks, including collection location, are pivotal to determine type and size of pancreatic stenting as well as approach using long-term transmural indwelling plastic stents. Pancreatography to adequately assess the main pancreatic duct may be performed by two methods: Either non-invasively using magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography or endoscopically via retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Despite the critical need to understand anatomy via pancreatography and assess the main pancreatic duct, a standardized approach or uniform assessment strategy has not been described in the literature. Therefore, the aim of this review was to clarify the role of pancreatography in the endoscopic management of encapsulated pancreatic collections and to propose a new classification system to aid in proper assessment and endoscopic treatment.

Key Words: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; Endoscopy; Endoscopic ultrasound; Pseudocyst; Endosonography; Pancreatic ducts

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic collections

Pancreatic and peripancreatic fluid collections (PFCs) are local complications due to acute or chronic pancreatitis and should be classified by the revised Atlanta Classification considering the time of presentation (more or less than 4 wk) and content (fluid alone or solid component). Before 4 wk, these collections are classified as acute, while after 4 wk collections are designated as late or chronic pancreatic collections. Once a fluid collection has become organized and developed a welldefined wall, these are then termed Encapsulated Pancreatic Collections (EPCs). EPCs are further subdivided into Pseudocyst – fluid containing only - and Walled-off Necrosis (WON) – containing the presence of fluid and a solid or necrotic content[1]. While a majority of these collections will resolve spontaneously, especially during the early phase (< 4 wk), persistent symptoms, complications, or infection may occur prompting treatment[2].

At present, there are 3 therapeutic approaches – surgery, percutaneous drainage and endoscopic drainage – for the treatment of EPCs, each of which may be used independently or in combination with another therapy. For many decades, surgery was considered the standard treatment modality and evolved from an open surgical technique to minimally invasive surgery, combining percutaneous drainage in a stepup manner[3]. More recently, the development of endoscopic drainage using endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) to achieve successful transmural drainage has overcome many complications related to surgery and percutaneous drainage and has demonstrated improved efficacy safety compared to more invasive approaches. At this time, endoscopic treatment of EPCs has become the first-line therapy for both pseudocyst and WON, when technically feasible[4,5].

Pancreatography

Since the 1970’s pancreatography by Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has been reported as a useful tool for the management of pancreatic pseudocysts. In 1979, Sugawaet al[6]demonstrated pre-operative endoscopic pancreatography was a preferred strategy among 83 patients prior to surgical treatment of pseudocysts. In 1988, Nordbacket al[7]again reported endoscopic pancreatography to be a useful tool to guide the best approach to PFCs, one that could predict response to percutaneous drainage or surgery. Since that time, from the 1990s and 2000s, pancreatography has helped clinicians determine if an endoscopic transpapillary approach could be performed[8-10]. In addition to the potential therapeutic approach by transpapillary drainage, pancreatography has being reported to be an important prognostic factor to determine treatment success and recurrence, especially when Disconnected Pancreatic Duct Syndrome (DPDS) is diagnosed[11,12]. Along with ERCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) has increasingly become a non-invasive alternative to assess the main pancreatic duct (MPD), especially when secretin-enhanced is available. MRCP has the additional advantage of evaluating the MPD distal to a complete disruption and the pancreatic parenchyma; however, this imaging modality continues to have a lower sensitivity when compared to endoscopic pancreatography[13,14].

Disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome

DPDS was first described in 1989 by Smedhet al[15]in a case series of three patients[15]. It can be defined by (A) a complete MPD disruption and (B) a viable pancreatic tissue upstream from the disruption, resulting in a collection or fistula[11,16]. Therefore, in order to properly diagnose DPDS it remains essential to adequately assess the MPD and pancreatic parenchyma, usually performed by MRCP or computerized tomography (CT) combined with ERCP. DPDS has a tremendous impact on potential treatment and prognosis of EPCs and directly affects outcomes such as clinical success, recurrence, need for repeat interventions - including surgery - and duration of hospital stay. Thus, proper recognition and diagnosis of DPDS is fundamental in order to achieve the best outcomes for EPCs[11].

Objectives

The objective of this study was to perform a literature review including current recommendations and best practices regarding pancreatography and classifications in the context of endoscopic treatment of EPCs.

This review will be structured in to three main parts. First we aim to discuss the background information regarding pancreatography for EPCs, followed by our proposed classification, where we describe and propose a new practical and simple classification for pancreatography findings and their therapeutics implications. Lastly, we compare all previous classifications and our new proposed one and detail how this will aid endoscopists in daily practice and further improve standardization within the medical literature.

METHODS

All studies describing findings of pancreatography and the resulting endoscopic management of EPCs were included in this review. A protocolized search of MEDLINE (viaPubMed) and Embase databases was performed through August 20, 2020.

The search strategy for MEDLINE was: “(Pancreatic duct OR Minor duodenal papilla OR Wirsung duct OR Wirsung's duct OR Cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic retrograde OR Cholangiopancreatographies, endoscopic retrograde OR ERCP) AND (Pancreatic pseudocyst OR Pancreatic pseudocysts OR Walled off necrosis)”. All types of study were included.

After the initial search, duplicate studies were removed and selected studies were examined for information including: Indication and moment of pancreatography, study modality (i.e., ERCP or MRCP), pancreatography findings and descriptors, pancreatography classification, and findings that directly influenced the plan to pursue an endoscopic approach. All relevant information was extracted using Excel spreadsheets for future analysis.

BACKGROUND

Indication

Since most PFCs will resolve spontaneously, there was no indication measure to routinely evaluate the MPD. Although pancreatography is not always considered for the evaluation of EPCs, the general consensus at this time is that pancreatography should be performed for symptomatic patients with EPC that will undergo endoscopic intervention[11,17]. Yet, despite its importance, consensus and guideline recommendations remain highly variable. Currently, the European Society Gastroin-testinal Endoscopy (ESGE) recommends pancreatography for WON that undergo endoscopic treatment[18]; however, there are no recommendations regarding pancreatic pseudocysts. At present, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy does not comment on the topic or importance of pancreatography in its most recent guideline[2]. The Asian EUS group experts guideline implicitly recommends pancreatography suggesting pancreatic duct stent for partial disruption and acknowledging higher recurrence rates among patients with MPD disruption[19]. The rational to evaluate the MPDviapancreatography – either by ERCP or MRCP - for all cases of EPCs treated endoscopically is to appropriately assess for DPDS, and to assist endoscopists as to which lesions should or may benefit from treatment[20]. Thus, pancreatography may impact therapeutic, diagnostic, and prognostic outcomes for the management of EPCs and should always be performed in this context[21].

Time

The decision as to when to perform pancreatography remains a highly controversial topic. Many individuals may prefer pancreatography prior to endoscopic drainage[22], peri-procedurally at the same time as drainage[17], or post-drainage[23]. Authors advocating for pancreatography prior to drainage typically perform MRCP to evaluate both the collection and the MPD – allowing for information gathering, planning of the therapeutic approach, and potentially avoiding an unnecessary ERCP and complications related to it[20,24,25]. The rational for performing pancreatography at the same procedure as endoscopic drainage is to optimize the approach in a single procedure, which may result in a shorter hospital stay and lower overall cost[26]. It should be noted that this approach may not be feasible in cases of gastric outlet obstruction due to inflammation which may precludes passage of duodenoscope. In regards to pancreatography post-drainage, this strategy may provide the added advantage of increased accuracy given compression by the pancreatic collection and local inflammation may limit interpretation of the MPD prior to drainage[14,23]. Although concerns have been raised regarding ERCP in the setting of a PFC, studies have shown it to be a safe procedure with no negative impact[17]. Presently, the ESGE recommends pancreatography, either by MRCP (preferably) or ERCP, prior to transmural stent removal after endoscopic drainage[18]. At this time, there is no prospective study comparing the ideal strategy or time to perform pancreatography, with the decision largely driven by expert consensus, provider familiarity, anecdotal evidence, or institution protocol.

Study modality

As discussed previously, pancreatography should be performedviaeither ERCP (Supplementary Video 1) or MRCP[27]. CT has been reported as an option to evaluation of the MPD; however, its accuracy is less than ideal and not adequate to rule out MPD lesions[28]. Therefore, these authors do not currently recommend the use of CT to evaluate the pancreatic duct. At present, ERCP remains the gold standard to perform pancreatography due to higher sensitivity to detect ductal leaks when compared to MRCP and may be cost-effective and more convenient since it can be performed at this same time as other endoscopic procedures or drainage[14,23]. Yet despite these advantages of ERCP, it is not without certain limitations including the invasiveness of approach and risk for complications, including pancreatitis, bleeding, and perforation – and may not be able to accurately evaluate the MPD distal to a total disruption.

MRCP has the advantage of being a non-invasive exam, without significative associated adverse events and enables investigation of the MPD distal to a complete disruption and the pancreatic parenchyma – fundamental for the diagnosis of DPDS. Furthermore secretin-enhanced MRCP has been shown to increase the sensitivity for MPD disruptions[29]; however, this may not be widely available at most institutions. Currently, MRCP is recommended as the preferable method to evaluate the MPD after endoscopic drainage by the ESGE[18].

More recently, EUS has also been reported to be an effective alternative method to closely provide a detailed assessment of the MPD in the context of PFCs, although the sensitivity and specificity remains poorly evaluated to date[11,30]. Thus, these authors believe it is reasonable to perform a secretin-enhanced MRCP as the first line strategy to evaluate the pancreatic duct, if available[20]. Otherwise endoscopic pancreatographyviaan ERCP approach should be performed as the procedure of choice with patients fully aware of the potential for adverse events, though these remain acceptably low[17,31-34].

Descriptors

Despite the importance of pancreatography, description of findings is largely heterogeneous and not uniform in the current literature. Although some terms are often used by various authors and clinicians, terminology and descriptor language has not been standardized[35]. The most commonly utilized terms to describe abnormalities in literature are: Disruption (some authors dived into partial/incomplete and total/complete disruptions), disconnection, DPDS, transected, leak, fistula, rupture, stricture, stenosis, cut-off, obstruction and communication/non-communication with collection[9,13,14,18,19,22,36-40]. This heterogeneity may lead to confusion when reporting and interpreting data[8]. Although some terms are presumed to have the same meaning - such as partial disruption and partial leak, complete disruption and disconnection, cut-off and obstruction, stricture and stenosis – others seem to be uncertain - such as disruption, rupture, transection. It is also critically important to underscore that DPDS is an incorrect term to describe endoscopic pancreatography findings. The complete disruption of the MPD is one of two necessary conditions to diagnose DPDS. An image study showing a functional pancreatic tissue upstream to the complete disruption is necessary to define DPDS[11,40]. Therefore, ERCP alone cannot appropriately describe this phenomena; however, when pancreatography is performed by MRCP it is possible to diagnose DPDS since it allows study the MPD upstream the disruptions and the pancreatic tissue[13].

Classifications

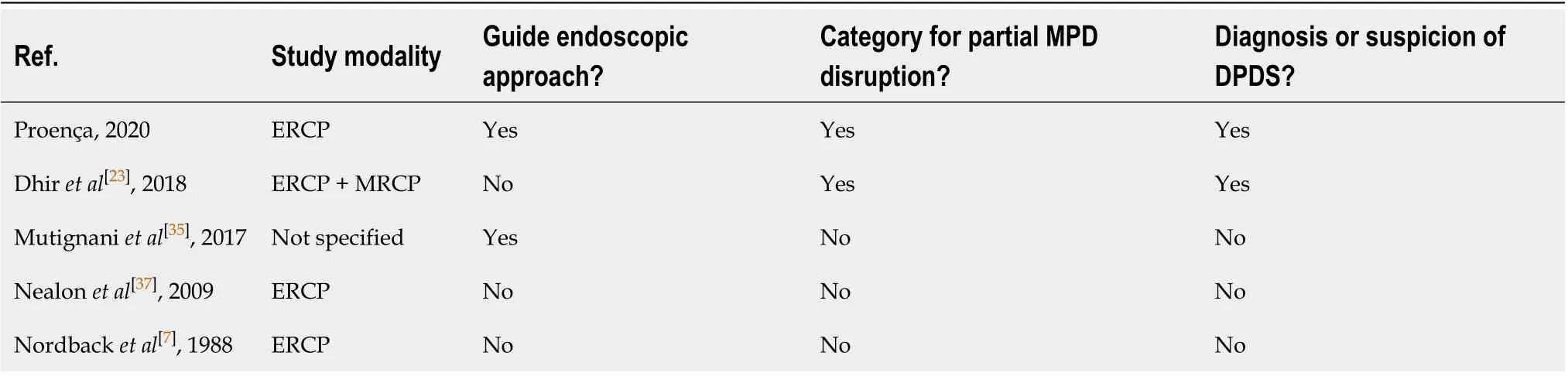

Five classifications on pancreatography findings have been described. The main characteristics of these classifications are summarized on Table 1. One was published in India[23], one in Italy[35], two in the United States by the same group[37,41]and one in Finland[7].

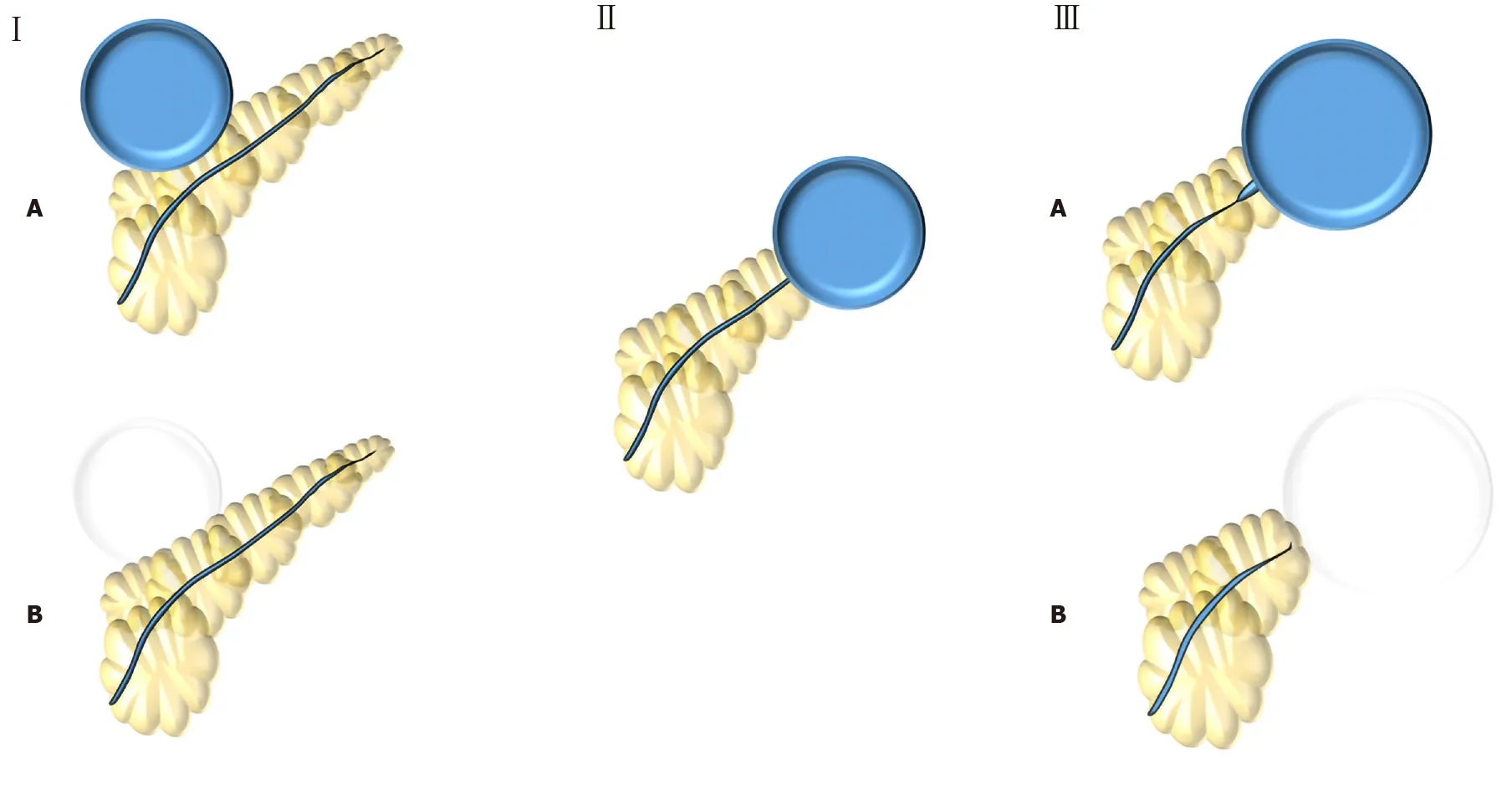

The first study to classify findings on pancreatography was a Finnish retrospective study published in 1988[7]. This group analyzed 15 patients with pancreatic pseudocysts who had undergone endoscopic pancreatography and were treated either by surgery or percutaneous external drainage. These authors then identified five patterns noted on pancreatography and classified these findings into three types, two of them with two subtypes (Figure 1). Based on the results observed, Nordback and colleagues suggested the best approach for each pancreatography type. Type I would benefit from percutaneous drainage, Type II from conservative management for 12 wk, and Type III from internal drainage (usually by surgery) or caudal pancreatic resection.

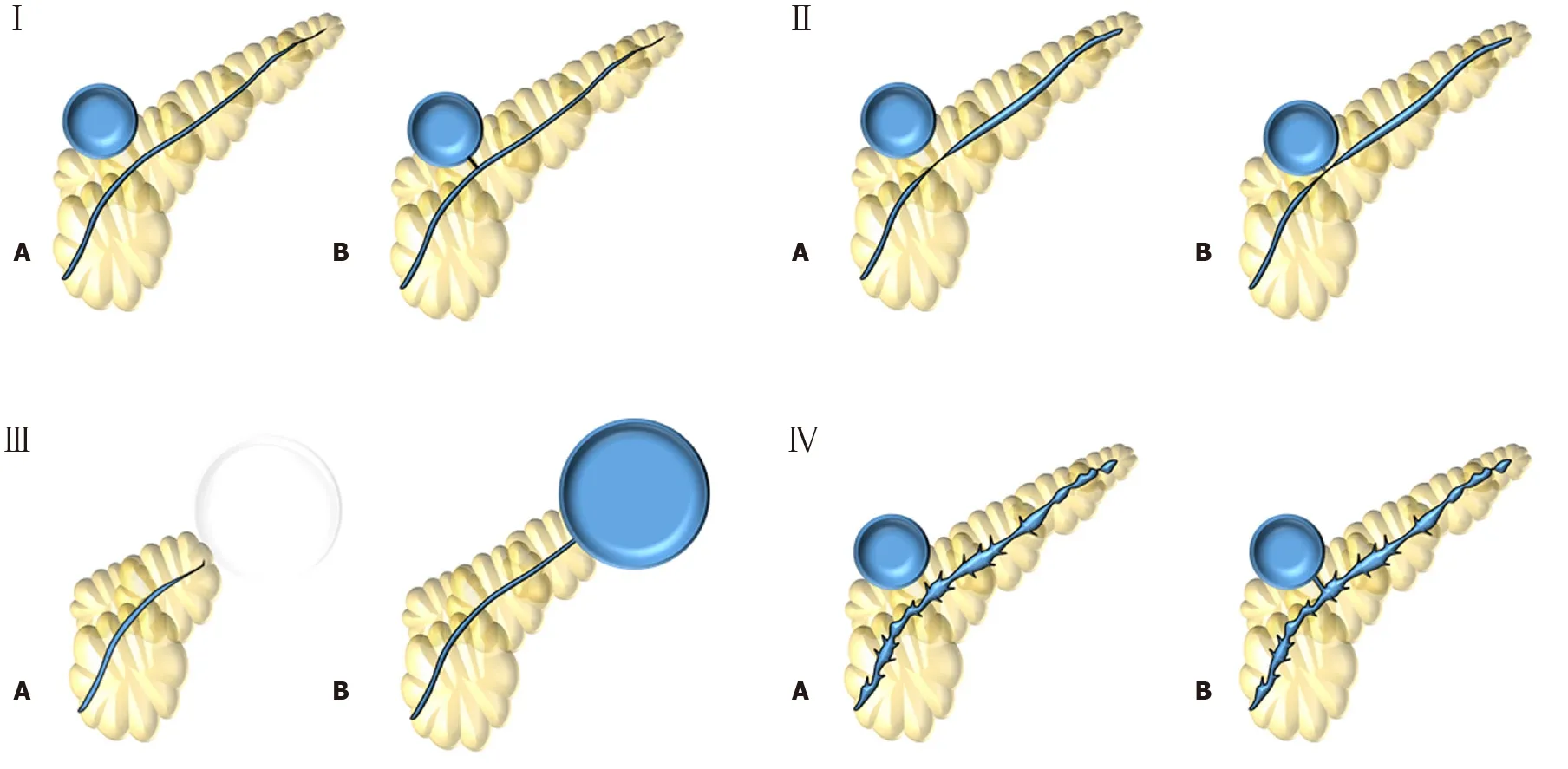

In the United States, Nealonet al[37,41]published two retrospective studies in 2002 and again in 2009, showing the impact pancreatography in the context of pancreatic pseudocyst to determine the best approach and estimate prognosis[37,41]. The second study[37], that can be interpreted as an updated of the first one[41], analyzed 563 patients with pseudocysts that underwent ERCP, MRCP, or contrast injection within an external drain placed percutaneous or surgically and described four pancreatography types (Figure 2). Type I findings would benefit most from endoscopic or percutaneous drainage; Type II recommending endoscopic management; and types III and IV planned for surgical intervention.

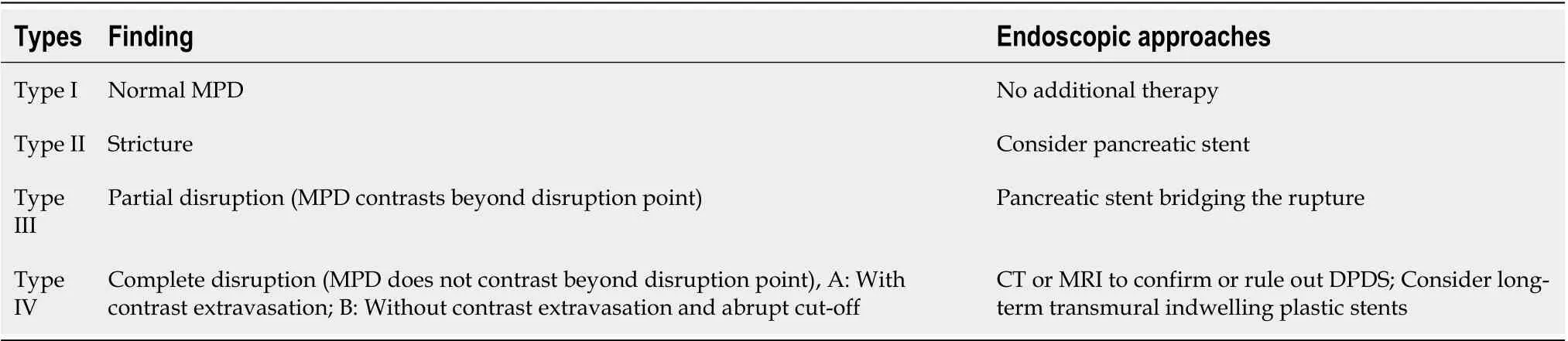

More recently, in 2017, Mutignaniet al[35]published a review on pancreatic fistulae and proposed a complete classification considering etiology and pancreatography, recommending an endoscopic approach for each type. These authors first divided pancreatic fistulas into three possible etiologies. Type I and type III were not related to pancreatitis and are beyond of the scope of this review. However, Type II were classified as injury to the MPD, usually related to PFCs and were dived into “open proximal stump” (IIO) and “closed proximal stump” (IIC) (Figure 3). For Type IIO, Mutignani and colleagues suggested bridging stent (first choice), transpapillary stent, or nasopancreatic drainage. For Type IIC, these authors recommended transmural EUS-drainage of the caudal collection with plastic stents, EUS-guided pancreaticogastrostomy, or a conversion to an IIO type and then treat accordingly.

In an prospective series of 88 patients with symptomatic WON, Dhiret al[23]demonstrated EUS-drainage with metal stents and pancreatography was performedviaERCP and MRCP. This group proposed four types on pancreatography using findings of ERCP and MRCP (Figure 4) and showed higher recurrence when there was MPD disconnection, regardless of whether WON was proximal (Type I) or distal (Type II) to the disconnection.

Approach to pancreatography findings

Endoscopic approaches based upon pancreatography findings continue to becontroversial. Some individuals advocate transpapillary drainageviapancreatic stenting for all MPD leaks and disruptions and combined with transmural drainage[20,21,23]. However, it should be noted that transpapillary drainage alone may be considered in specific cases where transmural drainage is not technically possible and there are favorable anatomical features – such as small collection, location in the head or uncinate process of the pancreas, and in cases with evidence of communication with the MPD[12,26]. A meta-analysis including 9 studies, with a total of 604 procedures, concluded that combined drainage with transmural and transpapillary approach does not have any benefits regarding technical success, clinical success, nor recurrence when compared to transmural drainage alone[42]. These findings are important but highly contestable since the majority (7 out of 9) of included studies were retrospective and they did not analyze the results by different pancreatography patterns. Other studies have shown better outcomes when a partial disruption have been treated by pancreatic stent bridging of the MPD[21,43,44]with this strategy currently recommended by the Asian guidelines consensus and considered an option by ESGE[18,19,45].

Figure 1 Nordback et al[7] (1988) classification. Type I: Normal main pancreatic duct (MPD) contrasting (type IA) or not (type IB) the collection; Type II: MPD opens to the collection; Type III: MPD with stenosis contrasting (type IIIA) or not (type IIIB) the collection.

Figure 2 Nealon et al[37] (2009) classification. Type I: Normal main pancreatic duct (MPD); Type II: MPD stricture; Type III: MPD occlusion; Type IV: Chronic pancreatitis. All types are subdivided according if they have communication (subtype A) or not (subtype B) with the collection.

Figure 3 Mutignani et al[35] (2017) classification. Type I: Leakages from small side brunches in the pancreatic head (IH), body (IB) or tail (IT); Type II: Leak in the main pancreatic duct that may have an open (IIO) or close (IIC) proximal stump; Type III: Leaks after pancreatectomy that may be after proximal pancreas (IIIP) or distal pancreas (IIID) resection.

Figure 4 Dhir et al[23] (2018) classification. Type I: Disconnection in the neck/body region, with a ductal leak at the proximal end; Type II: Disconnected duct with a Walled-off Necrosis distal to the disconnection – not possible to ascertain ductal communication with collection; Type III: Ductal leak without disconnection; Type IV: Shows a noncommunicating Walled-off Necrosis, with no disconnection.

The optimal management of DPDS also remains controversial. Surgery is still the gold standard treatment, though it is associated with a considerable morbidity and cost[46,47]. Most authors agree that pancreatic stenting is not effective for DPDS and many advocate for long-term transmural indwelling plastic stents – also recommended by ESGE[13,18,48]. Although complications related to long-term transmural indwelling plastic stents have been reported, including migration, gastrointestinal obstruction, perforation, infection, and bleeding, these occurrences are usually mild. Thus, it is considered a safe and effective method to prevent recurrence in patients with DPDS[36,38,49]. EUS-guided transluminal-MPD drainage has been reported for external pancreatic fistulas and may be an option for selected patients with DPDS that possess a dilated MPD[50,51]. Recently, Bashaet al[52]questioned the real importance of transluminal indwelling stenting for DPDS in a study with 274 patients with WON that underwent endoscopic drainage[52]. These authors reported a recurrent rate of 13.2%, in which 97% had DPDS, but only 6.6% (17 patients) required reintervention. This study also suggested that patients with DPDS should be followed and treated if a symptomatic recurrent collection occurs instead of performing any treatment to prevent those recurrences.

Additionally, strictures of the MPD may be treated using pancreatic stenting[8,20,28,40,53]. Although this remains a reasonable approach, there is no comparative study demonstrating the impact of stricture treatment for EPCs management. Currently, the lack of prospective controlled studies comparing the role of pancreatography findings makes most the current recommendations weak with an overall low-quality of evidence. Therefore, it is necessary to standardize pancreatography findings for better communication and to enable high-quality prospective controlled studies considering those different findings in order to clarify the best endoscopic management towards MPD injuries in the context of EPCs.

NEW CLASSIFICATION PROPOSITION

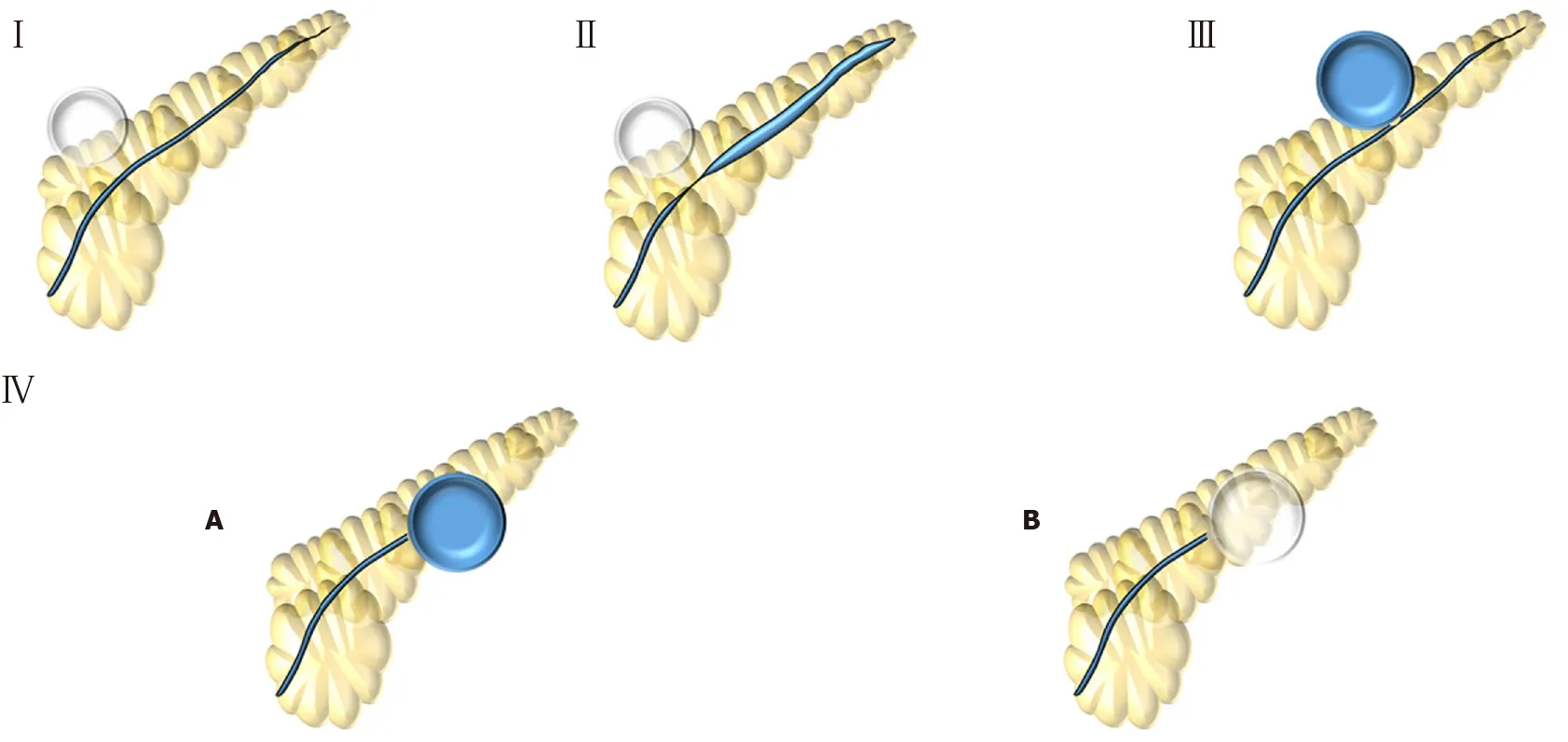

The classifications found in the literature, despite having value, are burdensome, overly complex, and difficult to apply during routine examinations. Therefore, the translation of these schemes to real-world clinical practice, or even standard for research reporting purposes has remained limited. As such, designing a simple, practical, and applicable classification system to standardize endoscopic pancreatography findings in the context of endoscopic treatment of EPCs is needed. Here we propose a new easy to apply classification for endoscopic pancreatography findings (Figure 5) with translation of these findings to impact endoscopic management (Table 2).

Type I involves a normal MPD, without stricture or disruption (Figure 6A). Therefore, no additional therapy is required. Type II demonstrates a stricture within the MPD (Figure 6B). We recommend treatment involving a pancreatic stent through the area of stenosis. Type III involves a partial disruption of the MPD – the MPD contrasts beyond disruption point (Figure 6C). In these cases, pancreatic stent bridging the rupture should be performed. Type IV shows a complete disruption of the MPD – the MPD does not contrast beyond disruption point. It may be presented with contrast extravasation (Type IV-A) (Figure 6D) or without contrast extravasation and abrupt cut-off (Type IV-B) (Figure 6E). Type IV should alert for the possibility of DPSP and an image study - such as CT or MRI - must be performed to confirm or rule out DPDS. If DPSD is confirmed, long-term transmural indwelling plastic stents should be considered. It is also critically important to recognize that more than one type may be presented simultaneously, such as a pancreatography demonstrating a stricture and a complete disruption with contrast extravasation (Figure 6F) - classified as a type II + IV-A.

DISCUSSION

Classifications are important tools used frequently in all fields of medicine, helping to categorize finding, standardize treatment-specific approaches, and facilitate ease of communication between providers. Furthermore, the better the attempt at classification (i.e., the ability for conditions to fit within pre-determined criteria), the more applicable and clinically relevant these can by to everyday clinical practice. Reviewing literature, there is not any current classification system allow for this to occur – further highlighting why no descriptions and increased confusion regarding the role of pancreatography is present in the literature.

It is well established that EUS-guided transmural drainage is the gold standard approach for both pseudocyst and WON[4,5]. Thus, pancreatography classifications that attempt to guide the best approach – surgery, percutaneous drainage, or endoscopic drainage - no longer have clinical relevance. At present, there is not sufficient evidence or data in the proposed classifications by Nordback[7]and Nealon[37,41], to guide clinicians and endoscopists regarding the best approach decision.

Since EUS-drainage is the gold standard treatment for EPCs, pancreatography classification should ultimately be used to determine the best endoscopic approach. Mutignani′s classification[35]is the only one among the previous classification systems that attempts to guide endoscopic approach accordingly to the findings. Yet despite this, limitations remain.

The endoscopic approaches towards MPD remain controversial in literature since there is no prospective randomized trial comparing the decision to treat MPD lesions. While some retrospective studies and case series suggest better outcomes when a partial disruption of the MPD is treated with a bridging pancreatic stent[12,21,43,44], this data has not yet been studied in prospective studies. Additionally, another important point is to distinguish between a partial and a complete disruption of the MPD. Only the system devised by Dhiret al[23]dedicated a specific category (type III) for partial disruption of the MPD.

DPDS has been reported as an important condition that is underdiagnosed – related to an increased need for reintervention, surgery, longer hospital stay, and higherrecurrence[11,48]. Therefore, it remains essential that any pancreatography classification define and categorize lesions with increased ability to differentiate and diagnose DPDS. Among previous classifications, Dhir′s[23]was the only one to correlated properly pancreatography findings and DPDS.

Table 2 Lera-Proen?a new proposed classification for endoscopic pancreatography findings

Figure 5 Lera-Proen?a (2020) new proposed classification. Type I: Normal main pancreatic duct; Type II: Stricture; Type III: Partial disruption – main pancreatic duct contrasts beyond disruption; Type IV: Complete disruption - main pancreatic duct does not contrast beyond disruption. IV-A: with contrast extravasation or IV-B: without contrast extravasation and cut-off.

Our new proposed classification aims to determine the best endoscopic treatment based upon pancreatography findings, clearly distinguish between partial and total disruption and suggests cases which should warrant investigation for DPDS. Additionally, this classification system as designed by these atuhors is based upon on endoscopic pancreatography findings, making it easier and more applicable than Dhir′s classification that requires additionally imaging with MRCP. A comparative table between all classifications and the crucial points is presented in Table 3.

CONCLUSION

Evaluation of the MPDviapancreatography in the context of endoscopic treatment of EPCs may provide diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic implications and should therefore be performed for all cases. This may be performed by ERCP or MRCP, preferably with contrast-enhanced secretin when available. While optimal timing (predrainage, peri-drainage, or post-drainage) has not been determined, assessment of the duct, regardless of when, remains key. Although some pancreatography classification have been proposed, none is widely used in literature, likely due to non-standardized approaches or outdated practices not relevant to the modern endoscopist for the management of EPCs. Additionally, it is critically important to understand the significance of DPDS, make a clear distinction between partial and complete MPD disruption, and determine the best endoscopic approach based upon pancreatographyfindings. Therefore, we propose a simplified and practical classification system to report the findings of pancreatography, improve uniformity for future research, inform guidelines and clinical management, and ultimately guide endoscopic treatment of EPCs.

Table 3 Comparation between pancreatography classifications

Figure 6 Endoscopic pancreatography classified by Lera-Proen?a classification. Endoscopic pancreatography findings, A: Normal pancreatography (type I); B: Stricture (type II); C: Partial disruption (type III); D: Complete disruption with contrast extravasation (type IV-A); E: Complete disruption without contrast extravasation and cut-off (Type IV-B); and F: Stricture and complete disruption with contrast extravasation (Type II + IV-A).

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年45期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年45期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Chinese guidelines on the management of liver cirrhosis (abbreviated version)

- Altered metabolism of bile acids correlates with clinical parameters and the gut microbiota in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome

- Alteration of fecal tryptophan metabolism correlates with shifted microbiota and may be involved in pathogenesis of colorectal cancer

- Relationship between the incidence of non-hepatic hyperammonemia and the prognosis of patients in the intensive care unit

- Endoscopic mucosal ablation - an alternative treatment for colonic polyps: Three case reports

- Tuberous sclerosis patient with neuroendocrine carcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: A case report